1773 - Setting the Stage for the Boston Tea Party

British tea sales in the Colonies have dropped 70% since passage of the Townshend Acts in 1770.

In May, the British Parliament passes the Tea Act in an ill-fated attempt to prop up the financially struggling British East India Company, which has 18 million pounds of unsold tea sitting in its warehouses.

Although the Tea Act actually reduces the tax on tea, it creates a monopoly by forcing the Colonists to buy only from the East India Company.

Why is this a problem? Easy - the East India Company ships directly from India, by-passing London merchants with whom the Colonists have trade agreements.

Furthermore, the Tea Act stipulates that the tea can be sold in the colonies only by British-selected agents in the colonies, further cutting into the profits of local colonial merchants.

Did the British think that lowering the tariff would cause the colonists to overlook the other provisions? If so, they thought wrong!

Top Photo: Giant tea pot overlooking City Hall Plaza - a Boston landmark!, (c) Boston Discovery Guide

Boston Discovery Guide is a reader-supported publication. When you buy through our links, we may earn a commission at no additional cost for you. Learn more

What Was the Real Issue Between the Colonists & the British?

So was the real issue taxes?

Not really...the Tea Act would have lowered taxes. No, the real issue was the Colonists' profits, which the Tea Act would have reduced.

In September, British ships carrying 500,000 tons of tea depart from England for the colonies, setting in motion a series of events that will not end well for the king.

Tensions Grow Stronger

To the Colonists, the tea tax is a test.

They tell themselves that if they pay it, they'll confirm Britain's right to tax them - of course, the British have already been taxing them, but of course the real "cost" to the Colonists is loss of free trade.

Because the English government declared that tax will be owned the moment that the Colonists unload the tea onto the docks, they resolve that the tea must not be unloaded.

The British, an ocean away and out of touch with the mood in the colonies, imagine that the Tea Act will be received warmly by colonists. Since they don't question their right to tax the colonists, they don't realize the strength of the colonists' feelings about taxation by a distant power. Perhaps not realizing how much smuggling has been going on, the British even imagine that the colonists will be happy to have their tea supply restored.

As a result, the heat of the colonists’ anger catches them off-guard.

“Anger” is an understatement.

The Colonists Send Back the Tea Ships

In Philadelphia and New York, colonists send the tea ships back to London. In Annapolis, an incensed crowd forces the ship’s frightened captain to burn his cargo and his ship. But in Boston, British Governor Thomas Hutchinson decides to stand firm.

The first tea ship, the Dartmouth, arrives in Boston on November 28th carrying a load of Darjeeling. Two more ships quickly follow.

In a public show of defiance against the British authorities, Samuel Adams and other Bostonians prevent the tea - 60 tons all together - from being unloaded.

In an equally public show of non-capitulation against the rebellious Colonists, Hutchinson, who happens to be related to the local British-appointed tea agents, keeps the ships in Boston Harbor and insists that the cargo will be brought ashore and taxed.

The Colonists Propose a Compromise - And the British Refuse

During the 3 weeks leading up to December 16, colonists meet almost daily in the Old South Meeting House (now a museum on Boston's Freedom Trail) to try to find or negotiate a legal way to not pay the tax.

The Colonists formally approve a resolution requesting that the local British-appointed tea agents refuse delivery of the tea and send the ships back to England.

The tea agents - including Governor Hutchinson's relatives - refuse.

On December 16th, the deadline for paying the taxes, Francis Rotch, a Nantucket Quaker and owner of the Dartmouth, agrees to sail his ship back to England and requests permission from Hutchinson to pass freely through Boston Harbor. Instead of easing tensions by allowing the ship to leave, Governor Hutchinson denies permission to clear the port.

Revolution against the British Begins

The Colonists Gather in the Old South Meeting House

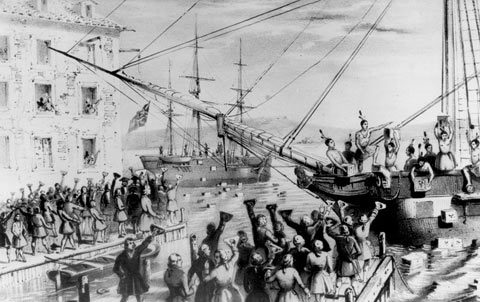

On the evening of December 16th, 5,000 or more Colonists gather in the Old South Meeting House, tensely waiting to learn if Hutchinson will permit the three ships carrying British tea to leave Boston Harbor and return to England.

Scattered throughout the men, women, and children packed into Old South are members of the Sons of Liberty, a group of Colonists opposed to English rule and taxation.

After dark, Rotch returns from his meeting with Hutchinson and reports that he cannot depart. And that's when Patriot Samuel Adams shouts the secret code words to the crowd in the Old South Meeting House, "This meeting can do nothing more to save the country!"

Hearing this prearranged secret signal, the Sons of Liberty leap into action.

Thanks to the elaborate planning behind this seemingly spontaneous event, groups converge from at least 10 different locations: taverns, shops, clubs, even houses.

Hastily disguising themselves, some as Mohawk Indians, Sam and about 150 others race down to Griffin's Wharf (now the site of the splendid InterContinental Hotel Boston) where the ships were anchored. Many other Patriots join them along the way.

In the darkness, they divide into 3 groups, each boarding one of the three ships. Working fast and in close cordination, they move 342 chests of tea, each weighing up to 360 pounds, and dump a total of 50 tons of fine British tea worth $1 million in today's dollars into Boston Harbor where British warships hovered just 1,500 feet away.

And on this evening, the Colonists' revolution against British rule began. Today, we call this pivotal event in American Revolutionary history the "Boston Tea Party."

Can you still visit the site of the Boston Tea Party today? Yes, you can - but there's really not much to see other than a small plaque on the side of the InterContinental Hotel's parking garage. The best place to get a sense of the event is the nearby Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum which offers immersive experiences and lots of fun special events.

1774 - Retribution: What Happens after the Boston Tea Party?

To retaliate for the Boston Tea Party, the British pass what the Colonists quickly dub “The Intolerable Acts.”

These laws ban all unapproved town meetings in Massachusetts, close the Port of Boston until the Colonists reimburse the cost of the dumped tea, declare Salem rather than Boston to be the capital of Massachusetts, and most insulting, allow British troops to move into Massachusetts houses or buildings without the permission of the owner.

Designed to break the spirit of the colonists and financially punish the unruly Bostonians, the Intolerable Acts instead inflame revolutionary fervor to an incendiary pitch.

However, to the colonists' glee, the Boston Tea Party does cause the hasty departure of one "guest": Thomas Hutchinson is replaced by General Thomas Gage as British Governor of Massachusetts.

Fun Fact about the Boston Tea Party

From 1773 forward for the next 62 years, people refer to the events on the night of December 16th as "The Destruction of the Tea."

Finally, in 1835, the Sons of Liberty's bold actions start being called "The Boston Tea Party."

Find out what happens next: The American Revolution Begins

Find Out More about Boston's History on these Fun Tours

More Articles about Boston History

- What happens next: the American Revolution begins!

- Boston's historical Freedom Trail

- Fun Freedom Trail Tours

- Historic Boston bars and taverns that you can still visit today

- More on the Boston history Timeline